Sept. 2, 1945: The end of the Pacific war

The 15 days between Japan’s decision to accept unconditional surrender, Aug. 15, 1945, and the day the Japanese government and its military officials actually signed the surrender document, Sept. 2, were among the most dynamic days in Pacific history. The Allies did not trust the Japanese military to actually lay down their arms after years of fighting to the finish; death before dishonor. A military coup had been attempted on the evening of Aug. 14, but failed. War Minister Gen. Korechika Anami committed seppuku after signing the offer to surrender the evening of the 15th.

Disarming the Japanese military forces was problematic because they were stretched over millions of square miles of Asia. It was hard to get word to every unit. In the first few days, diehards took their frustration out on POWs. Some beheaded. Groups held in underground cells were burned to death. For the most part, however, the Japanese guards simply walked out of the camp and never looked back.

On Aug. 16, Marshall Stalin suggested to President Truman that Japanese forces in Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost home island, should surrender to Soviet forces. Truman had decided that Japan would not be partitioned, as had been Germany. He responded, “…arrangements have been made for the surrender of Japanese forces on the islands of Japan proper, Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu to Gen. MacArthur.” With that supreme decision, Truman set the stage for a lasting peace in the Pacific.

On the 18th, Gen. Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, advised Brig. Gen. Thomas Farrell, his deputy, who had been on Tinian for several weeks, that the bomb assembly teams would remain “in such a state of readiness that the reactivation time will be no, rept, no longer than it takes to fly the active material…from New Mexico to Tinian.” They wanted another bomb ready, just in case.

Gen. George Marshall, chief of staff, U.S. Army, informed Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, that an investigative group would arrive in Japan from Tinian to study the after-effects of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They should “enter these cities with the landing troops,” wrote Marshall.

MacArthur’s staff responded, not “before D-Day (the surrender), plus 26 at earliest.”

Gen. Spaatz fired back that “Dog plus twenty-six is not acceptable. Believe scientists should be landed on Dog plus one at very latest…”

Several dozen British, Dutch, and American senior officers including Lt. Gens. Jonathan Wainwright and A.E. Percival were located and liberated at the Hsian POW camp, 150 miles north of Mukden in northern China on Aug. 19th. Both would participate in the surrender ceremony.

Capt. Parsons, USN, reported to Gen. Farrell on Aug. 20 that three Fat Man bombs were ready on Tinian, waiting only for the active core. That same day, the Russians established a new atomic bomb research project.

By Aug. 26, 1945, a Gallop poll showed that 85% of the respondents endorsed the atomic bombing of Japan.

On Aug. 27, the first airdrops of food and supplies to POW camps on Japan’s home islands began. B-29s from the 58th, 73rd 313th, 314th, and 315th Bombardment Wings flew 900 sorties to 158 prisoner-of-war and civilian internment camps.

To reassure the Americans, Emperor Hirohito issued a “Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors on Aug. 28, stating “…members of the imperial family will be dispatched as personal representatives of his majesty to the headquarters of the Kwantung Army, Expeditionary Southern Regions, respective.” Their purpose was to ensure that the army, which had occupied Manchuria in 1931 and invaded China in 1937 without orders from Tokyo, obeyed the Emperor’s directives for peace. The Kwantung Army immediately ordered a cease fire.

On Aug. 29, U.S. Marines liberated the Omori POW Camp on a prisoner-built island in Tokyo Bay. The POWs were evacuated to the USS Benevolence, where the “walking skeletons” were registered, checked, cleaned, deloused, shaved, clothed, and fed whatever they wanted.

Gen. MacArthur left Okinawa on Aug. 30 aboard the C-54 Bataan and landed at Atsugi Air Base, outside Tokyo. There were only about a thousand American troops on the ground, with hundreds of thousands of Japan soldiers nearby. MacArthur stepped out the door of the plane, unarmed. Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote of it, “Of all the amazing deeds of bravery during the war, I regard MacArthur’s personal landing at Atsugi as the greatest of the lot.”

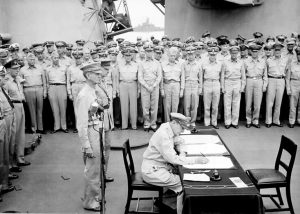

The surrender ceremony was held aboard “Mighty Mo,” the USS Missouri, on Sunday morning, Sept. 2, Tokyo time. The flag that had flown over at the U.S. Capitol on Dec. 7, 1941, flew from the ship’s masthead.

Hirohito released another Imperial Rescript: “We command all Our people forthwith to cease hostilities, to lay down their arms and faithfully to carry out all the provisions of the Instrument of Surrender and the General Orders issued by the Japanese Imperial Government and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters.”

After directing the ceremony and having the Japanese officials sign the documents of surrender in front of Wainwright and Percival, Nimitz, Halsey and Mitscher, Gen. MacArthur gave the brief closing remarks:

“Today the guns are silent. A great tragedy has ended. …And so, my fellow countrymen, today I report to you that your sons and daughters have served you well and faithfully, with the calm, deliberate, determined fighting spirit of the American soldier and sailor, …They are homeward bound—take care of them.”

To make a final point to the Japanese officials still on the deck of “Mighty Mo,” American airpower arrived. With P-51 Mustangs from Iwo Jima leading the way, hundreds of B-29 Superfortresses cruised over the Missouri and the mighty fleet surrounding it at 3,000 feet. It was a fitting end to the war.

Gen. Farrell and his scientists entered Hiroshima the next day with Geiger counters.

Don Farrell (Special to the Saipan Tribune)

Don Farrell is author of the acclaimed book Tinian and The Bomb, available online at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07BMTVF1K. Book is also available at Bestseller Books and American Memorial Park Gift Shop.